By Hayley Thomas - Photos by Kaori Funahashi

New Times Cover Story Published in San Luis Obispo New Times June 10, 2015

Like the crash of surf onto sand, Neal Maloney remembers the exact moment his calling hit him. The recent Oregon State University Marine Biology graduate was scuba diving 60 feet below the Sea of Cortez, surrounded by baskets of Mexican Black Pearl Oysters. A blue-green expanse stretched out in all directions. The water was a balmy 84 degrees.

“I was holding a buoy rope, looking up and watching huge schools of sardines and schools of tuna swim all around,” Maloney said. “I remember thinking, ‘This is it. I can do this.’”

Donning a ball cap and T-shirt, Maloney looked all the part of a laid back surfer when he picked me up on a hot, bright day at the lapping edge of the Morro Bay Marina. No small talk—certainly no life jackets—would be happening today. I was going to live like a sun-weathered oyster farmer, if only for an afternoon.

The skiff cut through the water at 30 miles per hour, wind and spray rendering my digital recorder useless. Over the roar of a sputtering engine, Maloney waved his arm to indicate that these glittering waters—134.5 leased acres to be exact—serve as his “office.” As owner of Morro Bay Oyster Farm, Maloney’s days begin at dawn and blur into a patchwork of gentle waves, shrieking seagulls, shy harbor seals, and bags of hard, bumpy shells.

“You are on a mud flat, and it may look barren, but there is a lot going on under the surface—clams, worms, shrimp," Maloney said. "An oyster’s goal in the wild is to grow as much as possible, and we are growing in an estuary, which is basically a nursery for the ocean.”

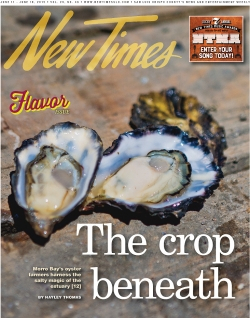

And it’s not just any nursery. Morro Bay's rich, cold seawater is bolstered by freshwater streams that flow from ancient volcanic aquifers. Phytoplankton is plentiful, and Intertidal beds of flat mud rise and fall with the tide. This is where plump, hardy Pacific Oysters thrive.

‘The office’

Water splashed the side of the skiff as Maloney docked against Morro Bay Oyster Company’s working platform, surrounded by rows of submerged oyster bags connected to long floating lines. I learn that there are 5,000 bags in the water, each containing 150 oysters. About 1 million oysters surround us at that very moment.

The water is shallow here—you can stand in it during most parts of the day. At high tide, the bags undulate in the chilly water. Come low tide, the oysters rest on a sandy bar. This constant movement encourages young, fingernail-soft oyster shells to transform into deep, layered cups.

Welcome to the world of aquaculture, where science, ocean, and farming collide.

“These are our crops. We have rows of oysters, just like you might have rows of plants,” Maloney said. “What we do is so much closer to farming than fishing. There are different life cycles of our product. Just like when you plant a seed—you have to take care of it, nurture it, grow it, and eventually, harvest it. The beautiful thing about our product is that it has a longer life. If I can’t sell it today, I can sell it tomorrow.”

On the working barge, three crewmembers—a surfer and a Cal Poly Marine Biology graduate among them—busied themselves hand grading and sorting. A mound of shiny black shells glittered on a wooden table, awaiting a keen eye and gloved hand. Back-dropped by a distant Morro Rock, I watched as the crew swiftly tackled the pile, sending each morsel into one of two routes.

These experts look for overall size, quality, shell depth, and shell thickness. It's time-consuming work, but that’s small price to pay to be able to paddle board to work. Underdeveloped oysters return to the mesh bags; those that get the green light earn a fast track to Morro Bay Oyster Company's salty holding area. This is the waiting room that stands between the sea and your stomach. But before you slurp—you should know that your dinner was more than two years in the making.

An oyster’s lifecycle

Maloney reached his hand into his bath tub-sized "oyster nursery" located on the Embarcadero, pulling up a fistful of Pacific Gold oysters no larger than pencil erasers. Amazingly, thousands of the living creatures can fit in just his two open hands. Maloney purchases his seed from approved hatcheries in Humbolt Bay and Quilcene, Washington. The species of Pacific Oyster—Cassostrea gigas—is originally from Japan.

Here, in Maloney’s nursery, the oysters live their first six to eight months. The newborns, so small they could slip through a window screen, are monitored daily to ensure they’ll grow healthy enough to withstand the harsher waters of the estuary.

Maloney showed me another nursery that cleverly floats just under a dock near the Embarcadero. A stone's throw from the company's fleet of boats, Maloney laid down on his belly and lifted a trap door, revealing thousands of 6-month-old shells no larger than a quarter.

"They chill here then go through a tumble sorter. The little ones fall through the mesh, and we put them back in the nursery," Maloney said. "No one really knows this is even here."

This last line resonated with me. How many locals are really acquainted with the local oyster industry, which quietly thrives just under our noses? Maloney remembers a time when there was “virtually no local market for oysters.” Now, restaurants like Artisan in Paso Robles serve them up fresh with a twist of lemon.

After eight months in the nursery, the young oysters are ready to go out into the farm waters, where they dine on the natural phytoplankton that flows freely through their new mesh bag homes. Flash forward another year to 18 months, and the oysters are ready for sorting and harvesting.

Technically, Maloney farms about 30 acres of the lease, and he’s working to expand that number. Gaining government approval to farm the surrounding waves requires a lengthy three-year testing process on top of regular, rigorous testing.

From what I could see with my own eyes, Maloney has enough work on his hands. Morro Bay Oyster Company can’t keep up with demand, which Maloney says, “is a good problem to have.” The business, established in 2008, sold 600,000 oysters last year and is on track to sell between 750,000 and 1 million this year. And although Central Coast’s farm-to-table chefs have caught on to the local oyster scene, these morsels aren’t homebodies. Maloney’s Pacific Golds gleam under glass at Whole Foods Markets across the west.

Not native, but welcome

Back on the barge, Maloney rolled over a newly-harvested bag of oysters, sending a crab scuttling into the sun—an indicator that so much is happening just below the surface of the water.

"I see an abundance of marine life benefitting from the growing structures," Maloney said. "The oyster bags offer fish a reef. When you pull our bags up, you see thousands of crabs and shrimps and worms that maybe wouldn’t have been as abundant in that area.”

Although oysters are not native to the bay, Maloney says they have a way of bringing biodiversity to the seascape. Like corn in North America, oysters in Morro Bay can only exist with human intervention.

This is not a new revelation: Since the early 1900s, farmers have purchased seed and transplanted it to hospitable waters across the state. According to The California Oyster Industry website, California served as the leading Pacific oyster producer during the latter part of the 1800s, followed closely by Washington. After the decline of the San Francisco Bay oyster industry (which attempted to transplant oysters from the east coast), farming production tanked.

George League, owner of Great American Fish Company in Morro Bay, remembers when oyster farming boomed again. During the 1950s, his family's business, El Morro Oyster Company, farmed the Morro Bay Waters with soaring success. Working 16 hour days that ended in processing and canning, League’s family utilized the same method farmers had used more than 50 years prior.

"The seed was brought in from Japan and we'd plant them just by shoveling off a barge into an oyster bed right on the ground. In two years or so, they'd be ready to be processed," League said. "We picked them by hand, putting them in large tubs when the tide was out. It was hard, heavy work."

If the tide was out in the middle of the night, or in the middle of a rainstorm, you better bet League was out there "picking oysters."

Every drop counts

When I called George Trevelyan of Grassy Bar Oyster Company—the second of Morro Bay's only two oyster farms—he was gearing up for the Avila Beach Oyster Festival. Despite a hectic week, he spoke to me from his own working barge in the estuary.

Trevelyan leases 158 acres, farms 10, and is also in the process of testing new water for government approval. He and his crew of four tend to a floating crop of about 2 million. Last year, the company sold a record-breaking 700,000 oysters, which are enjoyed locally and distributed by Santa Monica Seafood to restaurants from Monterey to San Diego. Trevelyan's operation, established in 2009, is similar in basic ways to his competitor's: He uses mesh bags to grow Pacific Oysters, and everything is hand-sorted and inspected. The two deviate in just how they stress the bags—Maloney allows the waves to do it for him while Trevelyan physically flips each bag during low tide.

Oyster farming makes little negative environmental impact, according to Trevelyan. You don’t feed them—they eat the natural phytoplankton. You don’t water them—they live and breathe the sea. There’s no spreading of pesticides. Aside from a few brave sting rays, oysters live peaceful, uneventful lives. Humans—and human pollution—are their only real concern.

"Both Neal and my operations are dependent on clean, pristine seawater," Trevelyan said. "Oysters, as filter-feeders, are very heavily regulated by the state health department. We work together to fight for clean water and strong environmental rules that protect the estuary."

According to Trevelyan, many acres of water were shut down to farming use in the mid 90s due to poor water quality. Now, both men are working to capture the data needed to reopen the region. Part of that fight means banding with the Morro Bay National Estuary Program, which works with local ranchers and business owners to ensure that pollutants don't end up downstream.

"The fact that there are two viable oyster companies in Morro Bay is testament to the entire community. It takes the cooperation of everybody," Trevelyan added.

Thanks also to a lack of heavy industry in the area, the water has continued to pass rigorous twice-monthly tests.

That being said, both farms are legally obligated to shut down their operations after rainfall exceeds a legally determined threshold (not so during George League's day). Before opening again, another test is required.

Although Trevelyan said working with these regulations can sometimes be frustrating, the work is ultimately satisfying.

"It's hard work, but it's fulfilling work," he said. "This really is my dream."

After harvest, the farmer lovingly moves oysters onto racks above the bay floor to purge any silt lurking in the shells. Like Maloney’s “sweet Pacific Golds,” Maloney feels his “Grassy Bars” are unique works of art that reflect a culmination of practices and environmental factors. The meat is known for its distinct watermelon flavor.

Morro Bay ‘Merroir’

Maloney showed me just how to insert a shucking knife—first, push it like a key into a keyhole, then diagonally to deactivate the hinge—before severing the membrane that connects the muscle to the shell. The meat tastes satisfyingly briny and slightly sweet.

Just as a winemaker may refer to the vineyard’s “terroir,” Maloney calls this convergence of land, water, and air “merroir.”

“That fresh water from the aquifers translates to sweet on your pallet, and when we do get rain and our oysters take in water with lower salinity, the oysters get a little bit sweeter still,” he said. "Morro Bay, all of this, comes together to make the flavor of our oyster."

If you want to taste the bay, all you need to do is schuck a shell for yourself. Winter rainfall causes the oysters to plump up as they store precious glycogen, bestowing a melon finish. At the end of summer, just before spawning, the meat is leaner, with saltier tang.

Like the oysters themselves, Moro Bay's oyster farmers are forever undulating, rolling with the primal rhythms of the ocean. Luscious meat hides just beneath the waves; it only takes an adventurous seafaring farmer to go out there and discover it.

"When I was 5, my family would go to Mendocino, to the tide pools. I fell in love with the sea anemone, little crabs, fish," Maloney said. "I've always wanted to be out there, spelunking."